Public Awareness 2013

Media Coverage to Date:

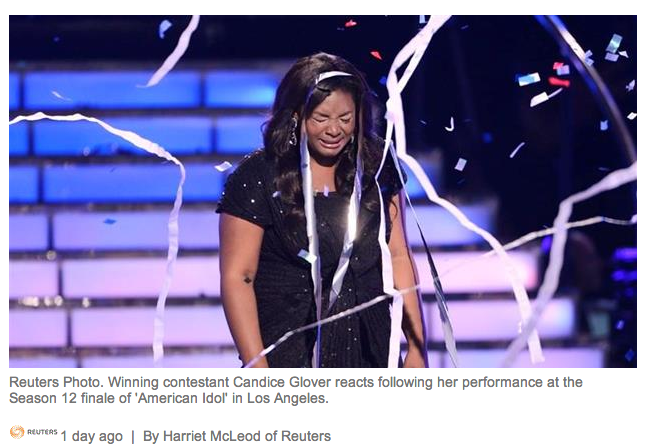

'American Idol' winner shines spotlight on South's Gullah Geechee culture

The culture of an island region in the South, descended from West African slaves, is being pulled into the national spotlight after Candice Glover's "American Idol" win.

CHARLESTON, S.C. — "American Idol" winner Candice Glover, whose powerful voice clinched the title of the popular TV singing show, comes from a sea island culture made up of descendants of West African slaves.

"I speak another language," she said during the Fox TV show. "It's called Geechee."

Glover, 23, is a native of rural St. Helena Island in the coastal South Carolina Lowcountry. The island is part of a new national heritage corridor to preserve and promote the unique African culture and language called Gullah Geechee that survived on the isolated sea islands of South Carolina and Georgia for centuries.

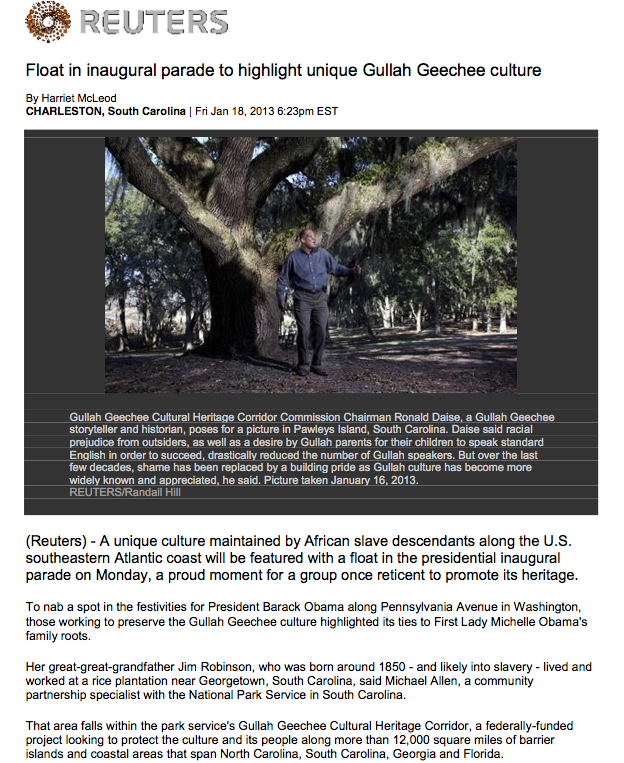

"When she said that, I stood up in my living room and applauded," said Ron Daise, commission chairman of the corridor that also includes parts of North Carolina and Florida. "There's a rootedness about her spirit."

The Glover family does not know the language, a mix of West African dialects and English, Glover's mother, Carole, said in an interview this week.

But she added that her daughter's revelation made residents of St. Helena "proud and happy."

Related: SC slave cabin will recreate history at new Smithsonian museum

In April, Daise wrote Glover a congratulatory letter that ended in Gullah: "We stan op an clap clap clap clap cuz oona da one a we! A kno de Lawd done lay E han pon oona."

The oldest of seven children, Glover was 4 years old and singing solos in church when her parents first noticed her talent. When she was eight, she got a standing ovation.

"She always got solos because, you know, she has the voice to take us there, into worship," her mother said. "It came from God, that's what I believe."

With no formal training, Candice entered talent shows, made YouTube videos in her living room and auditioned for "American Idol" twice and was cut. She was working at a beach resort when she made it onto the show with her third try.

Supporters on St. Helena Island sold T-shirts and pins to send Glover's parents to California to watch her perform. Her mother is a former daycare worker, and her father, John, is a truck driver. Bars in the nearby city of Beaufort created and served Candy Cane Martinis for "Idol" parties.

Governor Nikki Haley proclaimed May 4, Glover's homecoming day from the show, "Candice Glover Day" statewide. A riverfront parade down streets featured a marching band and floats.

"She cried so much during that day, all through the parade she cried," her mother said. "Because this is a little country girl and this is her dream."

Glover's mother said she thought a high point of the "American Idol" season was her daughter's performance of "You've Changed," the jazz song made famous by Billie Holiday.

"My parents have always taught me to be humble in everything that you do and everybody has to start at the bottom," Glover told a South Carolina television station.

Asked what goes through her mind before a performance, she said, "the lyrics."

She starts a 40-city national tour, with 10 other "Idol" finalists, on June 29.

CHARLESTON, S.C. — "American Idol" winner Candice Glover, whose powerful voice clinched the title of the popular TV singing show, comes from a sea island culture made up of descendants of West African slaves.

"I speak another language," she said during the Fox TV show. "It's called Geechee."

Glover, 23, is a native of rural St. Helena Island in the coastal South Carolina Lowcountry. The island is part of a new national heritage corridor to preserve and promote the unique African culture and language called Gullah Geechee that survived on the isolated sea islands of South Carolina and Georgia for centuries.

"When she said that, I stood up in my living room and applauded," said Ron Daise, commission chairman of the corridor that also includes parts of North Carolina and Florida. "There's a rootedness about her spirit."

The Glover family does not know the language, a mix of West African dialects and English, Glover's mother, Carole, said in an interview this week.

But she added that her daughter's revelation made residents of St. Helena "proud and happy."

Related: SC slave cabin will recreate history at new Smithsonian museum

In April, Daise wrote Glover a congratulatory letter that ended in Gullah: "We stan op an clap clap clap clap cuz oona da one a we! A kno de Lawd done lay E han pon oona."

The oldest of seven children, Glover was 4 years old and singing solos in church when her parents first noticed her talent. When she was eight, she got a standing ovation.

"She always got solos because, you know, she has the voice to take us there, into worship," her mother said. "It came from God, that's what I believe."

With no formal training, Candice entered talent shows, made YouTube videos in her living room and auditioned for "American Idol" twice and was cut. She was working at a beach resort when she made it onto the show with her third try.

Supporters on St. Helena Island sold T-shirts and pins to send Glover's parents to California to watch her perform. Her mother is a former daycare worker, and her father, John, is a truck driver. Bars in the nearby city of Beaufort created and served Candy Cane Martinis for "Idol" parties.

Governor Nikki Haley proclaimed May 4, Glover's homecoming day from the show, "Candice Glover Day" statewide. A riverfront parade down streets featured a marching band and floats.

"She cried so much during that day, all through the parade she cried," her mother said. "Because this is a little country girl and this is her dream."

Glover's mother said she thought a high point of the "American Idol" season was her daughter's performance of "You've Changed," the jazz song made famous by Billie Holiday.

"My parents have always taught me to be humble in everything that you do and everybody has to start at the bottom," Glover told a South Carolina television station.

Asked what goes through her mind before a performance, she said, "the lyrics."

She starts a 40-city national tour, with 10 other "Idol" finalists, on June 29.

The temptation is to think that what follows here is the whole story. It’s not, of course. So much happened before the people who later settled in Savannah’s Pin Point community ever reached the shores of Georgia’s barrier islands in the 18th century, so much unfolded even before they were ripped from West Africa, chained and humiliated, and sold in the dusty markets of the new world.

But you have to start somewhere. You have to feel your way along the horizon of history, choose a time and place to pick up the thread and hope it does justice to all that came before.

That is the goal of a unique partnership of three historical sites stretching along the city’s Southside, sites linked not only by geography and purpose, but by their individual and cumulative histories.

SLIDESHOW: Coastal Empire Heritage Tour

In many ways, Ossabaw Island begat Pin Point and Pin Point lent its sea-roughened hands to the evolution of Bethesda Academy from one of the first orphanages in the new American colonies to a school of distinction and a petal in the flowering story of Savannah’s rural life.

“This isn’t just a story,” said Paul Pressly of the Ossabaw Island Education Alliance. “It’s an American story. In some ways, it’s all of our stories.”

On Friday, Pressly will join David Tribble, the president of Bethesda Academy, and Scott Smith of the Coastal Heritage Society at the Pin Point Heritage Museum in the inaugural event of their partnership that seeks to develop heritage and educational tourism in this region.

It seems a natural fit, from the scientific and artistic programs held on Ossabaw, where three tabby slave cabins still stand, to the white-washed splendor of the cozy Pin Point Heritage Museum on the former site of the Varn Oyster Co. along the marshes of the Moon River.

In between, there is the unique story of Bethesda Academy, where generations of Pin Point residents have worked since the Civil War and even attended as students after the school integrated.

The goal, according to those involved in the partnership, is to use their proximity and collective historical connections to develop unique heritage and educational programming at each of the sites that could combine to lure visitors from Savannah and beyond.

“I’m excited by the possibilities the partnership presents,” said Joe Marinelli, president of VisitSavannah. “Savannah’s visitors are generally cultural and heritage-type visitors. Most of that product is in the Historic District, so having this new product develop out on the coast is terrific because it begins to expand the Savannah experience a little bit deeper.

“It gives a little different perspective of the African-American culture and helps tell the more rural history of this area.”

The sites would continue to run independently but would share experiences and expertise in everything from marketing and facilities operation to the use of data bases and online tools.

“The three settings are all very attractive, natural settings,” said Smith, the president and chief executive officer of the Coastal Heritage Society, which oversees the Pin Point Heritage Museum. “They reflect a rural and coastal aspect of Chatham County. There are things relating to the African-American experience at Ossabaw and Pin Point and to another extent, Bethesda. But the story begins in the 1740s in West Africa and from there to Ossabaw.”

Ossabaw Island sits about 20 miles south of downtown Savannah by water or, on a calm day, a 25-minute ride by power boat from Burnside Island. It is roughly 10 miles long and seven miles across at its widest point. It is bordered on the east by the Atlantic Ocean, on the north by the Ogeechee River, St. Catherine’s Sound to the south and the Bear River/Florida Passage of the Intercoastal Waterway to the west.

Now the property of the state of Georgia, it has evolved into an offshore sanctuary for marine scientists and researchers, as well as communal gathering place for writers and artists under the guidance of the Ossabaw Island Foundation and the Ossabaw Island Education Alliance.

The first slaves showed up at Ossabaw in the mid-18th century to work the indigo plantations owned by John Morel Sr.

At the dawn of the Civil War, the approximately 230 slaves on the island moved to the mainland. About 150, now freedmen and women, returned after the war and worked as tenant farmers.

“At the end of the 1890s, a series of hurricanes come through,” Pressly said. “There may have been as much as eight feet of water on the island. They leave and create a descendant community at Pin Point.”

And that ushers in the second chapter of the story, a story told by the exhibits and artifacts in the Pin Point Heritage Museum.

“The people from Pin Point came from Ossabaw and the barrier islands,” said Tania Smith-Jones, site administrator at the Pin Point museum. “Bethesda has a connection to Pin Point as well. It’s amazing that we’re all finally coming together.

It is a tale both novel in its enterprise and common in its American spirit, a tale of a self-sustaining, spiritual, close-knit and free African-American community that carved out its existence not from the land, but from the sea.

“They actually purchased land in Pin Point just after those hurricanes,” said Elizabeth DuBose, director of the Ossabaw Foundation. “When you look at the deed, that’s when they occur, roughly from 1893 to 1896.”

The economic linchpin of the community, and central focus of the museum, is the workings of the Varn Oyster Co. It is through the story of that company and the transition of the Pin Pointers from farmers to watermen that the community’s story — and the Gullah-Geechee story — comes most clearly into focus.

Friday’s event, which will honor the regional Gullah-Geechee heritage, will include remarks by Joseph McGill, a Charleston, S.C.-based Civil War re-enactor and program officer for the National Trust for Historic Preservation and Emory Campbell , the former chairman of the Gullah-Geechee Cultural Corridor Commission, as well as Hanif Haynes , president of the Pin Point Betterment Association.

Following the program, there will be a tour of the Pin Point museum and a tour of the nearby recently completed Bethesda museum, which tells the history of the school within the context of Savannah’s emergence.

The Bethesda Museum is its own jewel. Housed in the first floor of Burroughs Hall, the collection of multi-media educational tools, artifacts and documents trace the history of the institution that is stretches back to 1740.

“This is a collection of like-organizations that have a real significant role in the history of this little area of Georgia, and it’s really great to come together and share those stories,” Tribble said of the fledgling partnership. “It brings together people who haven’t really worked together. In a way, we’re trying to create our own little bit of magic on Moon River.”

But you have to start somewhere. You have to feel your way along the horizon of history, choose a time and place to pick up the thread and hope it does justice to all that came before.

That is the goal of a unique partnership of three historical sites stretching along the city’s Southside, sites linked not only by geography and purpose, but by their individual and cumulative histories.

SLIDESHOW: Coastal Empire Heritage Tour

In many ways, Ossabaw Island begat Pin Point and Pin Point lent its sea-roughened hands to the evolution of Bethesda Academy from one of the first orphanages in the new American colonies to a school of distinction and a petal in the flowering story of Savannah’s rural life.

“This isn’t just a story,” said Paul Pressly of the Ossabaw Island Education Alliance. “It’s an American story. In some ways, it’s all of our stories.”

On Friday, Pressly will join David Tribble, the president of Bethesda Academy, and Scott Smith of the Coastal Heritage Society at the Pin Point Heritage Museum in the inaugural event of their partnership that seeks to develop heritage and educational tourism in this region.

It seems a natural fit, from the scientific and artistic programs held on Ossabaw, where three tabby slave cabins still stand, to the white-washed splendor of the cozy Pin Point Heritage Museum on the former site of the Varn Oyster Co. along the marshes of the Moon River.

In between, there is the unique story of Bethesda Academy, where generations of Pin Point residents have worked since the Civil War and even attended as students after the school integrated.

The goal, according to those involved in the partnership, is to use their proximity and collective historical connections to develop unique heritage and educational programming at each of the sites that could combine to lure visitors from Savannah and beyond.

“I’m excited by the possibilities the partnership presents,” said Joe Marinelli, president of VisitSavannah. “Savannah’s visitors are generally cultural and heritage-type visitors. Most of that product is in the Historic District, so having this new product develop out on the coast is terrific because it begins to expand the Savannah experience a little bit deeper.

“It gives a little different perspective of the African-American culture and helps tell the more rural history of this area.”

The sites would continue to run independently but would share experiences and expertise in everything from marketing and facilities operation to the use of data bases and online tools.

“The three settings are all very attractive, natural settings,” said Smith, the president and chief executive officer of the Coastal Heritage Society, which oversees the Pin Point Heritage Museum. “They reflect a rural and coastal aspect of Chatham County. There are things relating to the African-American experience at Ossabaw and Pin Point and to another extent, Bethesda. But the story begins in the 1740s in West Africa and from there to Ossabaw.”

Ossabaw Island sits about 20 miles south of downtown Savannah by water or, on a calm day, a 25-minute ride by power boat from Burnside Island. It is roughly 10 miles long and seven miles across at its widest point. It is bordered on the east by the Atlantic Ocean, on the north by the Ogeechee River, St. Catherine’s Sound to the south and the Bear River/Florida Passage of the Intercoastal Waterway to the west.

Now the property of the state of Georgia, it has evolved into an offshore sanctuary for marine scientists and researchers, as well as communal gathering place for writers and artists under the guidance of the Ossabaw Island Foundation and the Ossabaw Island Education Alliance.

The first slaves showed up at Ossabaw in the mid-18th century to work the indigo plantations owned by John Morel Sr.

At the dawn of the Civil War, the approximately 230 slaves on the island moved to the mainland. About 150, now freedmen and women, returned after the war and worked as tenant farmers.

“At the end of the 1890s, a series of hurricanes come through,” Pressly said. “There may have been as much as eight feet of water on the island. They leave and create a descendant community at Pin Point.”

And that ushers in the second chapter of the story, a story told by the exhibits and artifacts in the Pin Point Heritage Museum.

“The people from Pin Point came from Ossabaw and the barrier islands,” said Tania Smith-Jones, site administrator at the Pin Point museum. “Bethesda has a connection to Pin Point as well. It’s amazing that we’re all finally coming together.

It is a tale both novel in its enterprise and common in its American spirit, a tale of a self-sustaining, spiritual, close-knit and free African-American community that carved out its existence not from the land, but from the sea.

“They actually purchased land in Pin Point just after those hurricanes,” said Elizabeth DuBose, director of the Ossabaw Foundation. “When you look at the deed, that’s when they occur, roughly from 1893 to 1896.”

The economic linchpin of the community, and central focus of the museum, is the workings of the Varn Oyster Co. It is through the story of that company and the transition of the Pin Pointers from farmers to watermen that the community’s story — and the Gullah-Geechee story — comes most clearly into focus.

Friday’s event, which will honor the regional Gullah-Geechee heritage, will include remarks by Joseph McGill, a Charleston, S.C.-based Civil War re-enactor and program officer for the National Trust for Historic Preservation and Emory Campbell , the former chairman of the Gullah-Geechee Cultural Corridor Commission, as well as Hanif Haynes , president of the Pin Point Betterment Association.

Following the program, there will be a tour of the Pin Point museum and a tour of the nearby recently completed Bethesda museum, which tells the history of the school within the context of Savannah’s emergence.

The Bethesda Museum is its own jewel. Housed in the first floor of Burroughs Hall, the collection of multi-media educational tools, artifacts and documents trace the history of the institution that is stretches back to 1740.

“This is a collection of like-organizations that have a real significant role in the history of this little area of Georgia, and it’s really great to come together and share those stories,” Tribble said of the fledgling partnership. “It brings together people who haven’t really worked together. In a way, we’re trying to create our own little bit of magic on Moon River.”

By Tracey Teo

For the AJC

Posted: 12:25 p.m. Monday, April 29, 2013

Charleston, S.C. - At Boone Hall Plantation and Gardens in Mount Pleasant, S.C., a Charleston suburb, Jackie Mickel stands barefoot in front of an old slave cabin, her black hair tucked beneath a white turban, perhaps like her great-great-grandmother did when she was enslaved in Dorchester County approximately 25 miles inland.

But Mickel is here by choice, eager to reveal the mysteries of the Gullah or Geechee people, descendants of West African slaves that toiled on Lowcountry rice plantations in South Carolina and Georgia. Because they were isolated on the South Carolina Sea Islands for generations after the Civil War, the Gullah retained much of their culture and language– far more than any other group of African Americans.

The Gullah dialect, an English-based Creole language with a strong African influence, is incomprehensible to most Americans, so Mickel gives a brief Gullah vocabulary lesson before she tells the story of Brer Rabbit (Brother Rabbit), a witty character that often pops up in Gullah folklore to outsmart stronger, more powerful characters, like Brer Wolf and Brer Alligator. When these tales were told by slaves, white plantations owners were often the brunt of the joke, the character duped by a weaker but wiser one.Mickel explains that a “very soon man” is a wise man, and “before day clean” means early in the morning.

Mickel is a gifted storyteller, captivating the audience with her animated facial expressions and powerful voice. Her listeners are as spellbound as nursery school kids as she takes them along on Brer Rabbit’s adventures.

Boone Plantation dates back to 1681 and has passed through several owners. Tour guides in antebellum costumes lead visitors through the Georgian-style mansion that was built in 1936, (several houses have been on the site) but for some, the nine remaining slave cabins beneath towering Spanish moss-draped oak trees are more intriguing than the grand house with its elaborate antique furnishings.

Each cabin depicts a different aspect of slave life, such as musical and culinary traditions, and a knowledge of indigenous herbs used to make medicine and treat wounds.

In one cabin, a Gullah woman in a wide-brimmed hat patiently sews the sweetgrass baskets for which the area is famous. A centuries-old basket making tradition flourishes in the Lowcountry, a craft that can be traced to West Africa.

Once made by slaves for agricultural purposes, today the beautiful coiled baskets are much sought after by tourists as souvenirs.

Roadside basket stands dot U.S. Hwy. 17, a portion of the Gullah Geechee Cultural Heritage Corridor that runs along the southeastern coast from Pender County, N.C., to the southern border of St. Johns County, Florida.

There’s no shortage of plantation tours in the South, but few offer such an unflinching look at the injustices of slavery, while also celebrating the ingenuity and resourcefulness of those forced to endure it.

Gullah Tours

Go beyond Charleston’s antebellum mansions, bustling markets, and gleaming monuments and view the city from an African American perspective. Just hop on a bus with Alphonso Brown, owner and operator of Gullah Tours.

He delights in pointing out the wonders of the city that were “built, designed or created by blacks, but for whom credit was never given.”

Brown was raised by his grandparents in a rural community outside of Charleston, and he grew up with their Gullah language and traditions. At that time, the 1950s and ‘60s, Gullah were often ostracized as primitive and uneducated because they spoke “broken English,” now recognized as a separate language.“In my case, I’m no longer ashamed of my past or those from my past who shaped my future,” says Brown.

By the 1980s, Brown had embraced his heritage to such an extent he started a tour company to share it with others.

On the tour, Brown introduces tourists to Cabbage Row, the section of Church Street that inspired the fictional Catfish Row in Gershwin’s “Porgy and Bess.” Next he drives to the east side of town that was a crucial link in the Underground Railroad, a portal to freedom for slaves.

At a small frame house on Bull Street, Brown explains that the National Historic Landmark was the residence of Denmark Vessey, a freed slave who organized a failed slave uprising. Authorities discovered the plot and Vessey was hanged along with more than 30 co-conspirators.

A tour highlight is the home and workshop of Phillip Simmons, (1912-2009) a renowned Charleston blacksmith whose decorative wrought iron gates and balconies adorn the city. Unlike talented black artists and craftsmen in prior generations, Simmon’s work was widely recognized. He quite literally forged a name for himself in Charleston and beyond, winning numerous awards, including the prestigious National Heritage Fellowship.

Once marginalized and deprived of their rightful place in Charleston history, Gullah are celebrated today for their unique heritage that has helped shape the city.

For the AJC

Posted: 12:25 p.m. Monday, April 29, 2013

Charleston, S.C. - At Boone Hall Plantation and Gardens in Mount Pleasant, S.C., a Charleston suburb, Jackie Mickel stands barefoot in front of an old slave cabin, her black hair tucked beneath a white turban, perhaps like her great-great-grandmother did when she was enslaved in Dorchester County approximately 25 miles inland.

But Mickel is here by choice, eager to reveal the mysteries of the Gullah or Geechee people, descendants of West African slaves that toiled on Lowcountry rice plantations in South Carolina and Georgia. Because they were isolated on the South Carolina Sea Islands for generations after the Civil War, the Gullah retained much of their culture and language– far more than any other group of African Americans.

The Gullah dialect, an English-based Creole language with a strong African influence, is incomprehensible to most Americans, so Mickel gives a brief Gullah vocabulary lesson before she tells the story of Brer Rabbit (Brother Rabbit), a witty character that often pops up in Gullah folklore to outsmart stronger, more powerful characters, like Brer Wolf and Brer Alligator. When these tales were told by slaves, white plantations owners were often the brunt of the joke, the character duped by a weaker but wiser one.Mickel explains that a “very soon man” is a wise man, and “before day clean” means early in the morning.

Mickel is a gifted storyteller, captivating the audience with her animated facial expressions and powerful voice. Her listeners are as spellbound as nursery school kids as she takes them along on Brer Rabbit’s adventures.

Boone Plantation dates back to 1681 and has passed through several owners. Tour guides in antebellum costumes lead visitors through the Georgian-style mansion that was built in 1936, (several houses have been on the site) but for some, the nine remaining slave cabins beneath towering Spanish moss-draped oak trees are more intriguing than the grand house with its elaborate antique furnishings.

Each cabin depicts a different aspect of slave life, such as musical and culinary traditions, and a knowledge of indigenous herbs used to make medicine and treat wounds.

In one cabin, a Gullah woman in a wide-brimmed hat patiently sews the sweetgrass baskets for which the area is famous. A centuries-old basket making tradition flourishes in the Lowcountry, a craft that can be traced to West Africa.

Once made by slaves for agricultural purposes, today the beautiful coiled baskets are much sought after by tourists as souvenirs.

Roadside basket stands dot U.S. Hwy. 17, a portion of the Gullah Geechee Cultural Heritage Corridor that runs along the southeastern coast from Pender County, N.C., to the southern border of St. Johns County, Florida.

There’s no shortage of plantation tours in the South, but few offer such an unflinching look at the injustices of slavery, while also celebrating the ingenuity and resourcefulness of those forced to endure it.

Gullah Tours

Go beyond Charleston’s antebellum mansions, bustling markets, and gleaming monuments and view the city from an African American perspective. Just hop on a bus with Alphonso Brown, owner and operator of Gullah Tours.

He delights in pointing out the wonders of the city that were “built, designed or created by blacks, but for whom credit was never given.”

Brown was raised by his grandparents in a rural community outside of Charleston, and he grew up with their Gullah language and traditions. At that time, the 1950s and ‘60s, Gullah were often ostracized as primitive and uneducated because they spoke “broken English,” now recognized as a separate language.“In my case, I’m no longer ashamed of my past or those from my past who shaped my future,” says Brown.

By the 1980s, Brown had embraced his heritage to such an extent he started a tour company to share it with others.

On the tour, Brown introduces tourists to Cabbage Row, the section of Church Street that inspired the fictional Catfish Row in Gershwin’s “Porgy and Bess.” Next he drives to the east side of town that was a crucial link in the Underground Railroad, a portal to freedom for slaves.

At a small frame house on Bull Street, Brown explains that the National Historic Landmark was the residence of Denmark Vessey, a freed slave who organized a failed slave uprising. Authorities discovered the plot and Vessey was hanged along with more than 30 co-conspirators.

A tour highlight is the home and workshop of Phillip Simmons, (1912-2009) a renowned Charleston blacksmith whose decorative wrought iron gates and balconies adorn the city. Unlike talented black artists and craftsmen in prior generations, Simmon’s work was widely recognized. He quite literally forged a name for himself in Charleston and beyond, winning numerous awards, including the prestigious National Heritage Fellowship.

Once marginalized and deprived of their rightful place in Charleston history, Gullah are celebrated today for their unique heritage that has helped shape the city.

Publish Date: Feb 23, 2013, 04:13 PM ETDuration: 08:55

Click on image to view video

Chiefs defensive lineman Allen Bailey discusses growing up on Sapelo Island, Georgia and ponders the future of the dying historic community.

http://espn.go.com/video/clip?id=8978045

Tags: OTL, Outside The Lines, Chiefs, Allen Bailey, Sapelo Island, Georgia

http://espn.go.com/video/clip?id=8978045

Tags: OTL, Outside The Lines, Chiefs, Allen Bailey, Sapelo Island, Georgia

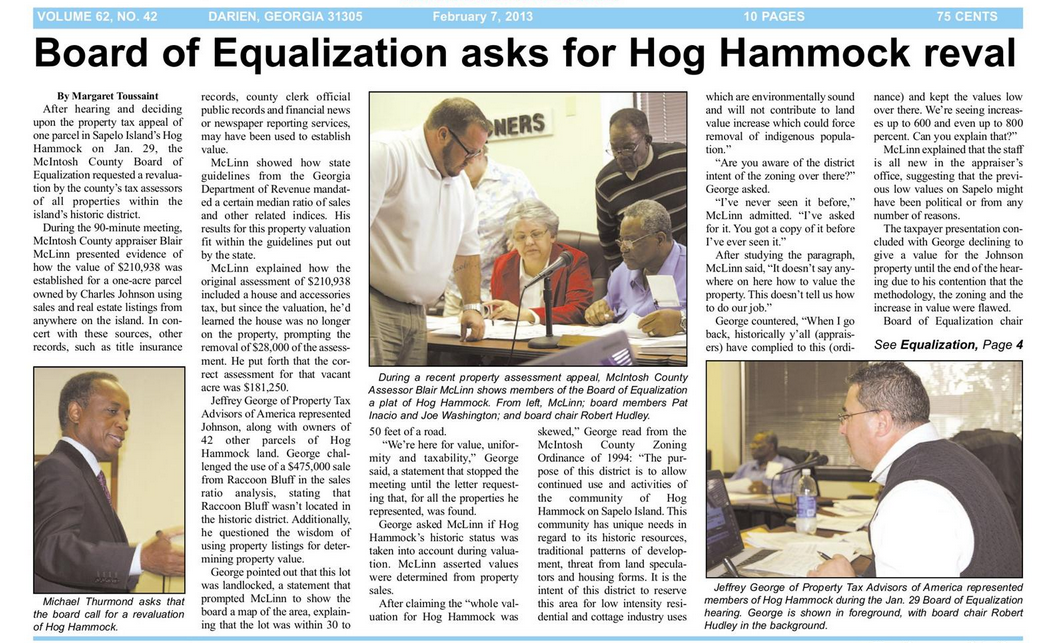

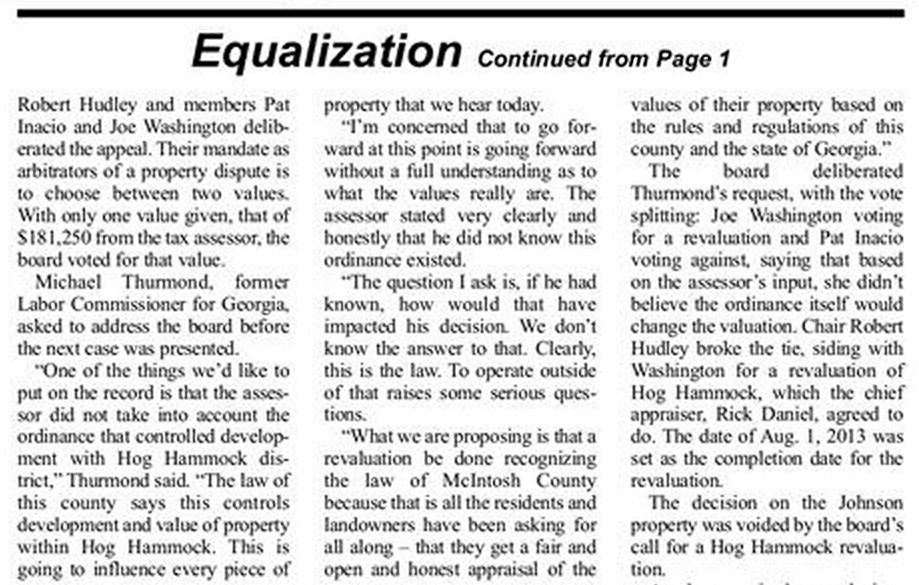

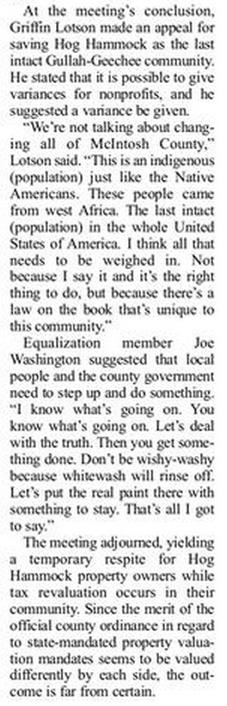

The Darien News

February 7, 2013

State of Georgia Senate

Jan/15/2013 - Senate Read and Referred - Natural Resources and the Environment

Jan/14/2013 - Senate Hopper

Senate Resolution 11

By: Senator James of the 35th

A RESOURCE

1 Creating the Senate Preservation of Sapelo Island Study Committee; and for other purposes.

2 WHEREAS, Greater Sapelo Island of McIntosh County, Georgia, is this state's fourth largest

3 barrier island and the home of important endangered wildlife, treasured historical structures,

4 and the vanishing culture of a significant community consisting of the Geechee Gullah

5 people; and

By: Senator James of the 35th

A RESOURCE

1 Creating the Senate Preservation of Sapelo Island Study Committee; and for other purposes.

2 WHEREAS, Greater Sapelo Island of McIntosh County, Georgia, is this state's fourth largest

3 barrier island and the home of important endangered wildlife, treasured historical structures,

4 and the vanishing culture of a significant community consisting of the Geechee Gullah

5 people; and

6 WHEREAS, approximately 97 percent of Sapelo Island is owned by the State of Georgia and

7 is managed by the Georgia Department of Natural Resources, while the remaining 3 percent

8 of the island is under private ownership; and

9 WHEREAS, the island also consists of the Sapelo Island National Estuarine Research

10 Reserve, the University of Georgia Marine Institute, and the Reynold's Mansion State Park;

11 and

12 WHEREAS, the Geechee Gullah people are the direct descendants of the slaves of Thomas

13 Spalding, who was the original landowner of Sapelo Island, and following the conclusion of

14 the Civil War, ownership of designated lands of the island were legally transferred to these

15 original freed men; and

16 WHEREAS, in 1983, Georgia law established the Sapelo Island Heritage Authority for the

17 purpose of preserving the culture in the endangered historical areas of Sapelo Island; and

18 WHEREAS, a severe erosion of Geechee Gullah culture and heritage has continued to the

19 point that it is in a state of near extinction; and

20 WHEREAS, extensive, unregulated commercial development of the island, without ethical

21 review or oversight, threatens not only the Geechee Gullah people but also the island's

22 beautiful natural resources and wildlife; and23 WHEREAS, such development has been for the personal, private gain of the few at the

24 expense of all of Georgia's citizens; and

25 WHEREAS, title to lands of the island is a matter of legal dispute, and the state's current

26 ownership may be the result of unjust enrichment at the expense of the Geechee Gullah

27 people; and

28 WHEREAS, the island has an abundance of historical property that is in need of state

29 funding for renovation and promotion as tourist attractions; and

30 WHEREAS, much of the island is composed of natural areas which need to be protected as

31 habitats for wildlife, nesting birds, and turtles in order to protect the beauty and tranquility

32 of this special state resource; and

33 WHEREAS, many concerned citizens, environmentalist groups, business and property

34 owners, and the original Geechee Gullah residents are gravely concerned about the future of

35 this beautiful island and the survival of its native people; and

36 WHEREAS, before it is too late and the important environmental and historical heritage of

37 the island is lost forever, the State of Georgia needs to immediately undertake an extensive

38 study and create a proposal for the development, funding, governance, and future of Sapelo

39 Island.40 NOW, THEREFORE, BE IT RESOLVED BY THE SENATE that there is created the Senate

41 Preservation of Sapelo Island Study Committee to be composed of seven members of the

42 Senate to be appointed by the President of the Senate. The President of the Senate shall

43 designate one of the members to serve as chairperson of the committee. The committee shall

44 meet at the call of the chairperson.

45 BE IT FURTHER RESOLVED that the committee shall undertake a study of the conditions,

46 needs, issues, and problems mentioned above or related thereto and recommend any actions

47 or legislation which the committee deems necessary or appropriate. The committee shall

48 review the following matters in particular:

49 (1) Building codes and zoning codes that may be needed for the protection of the

50 environment and the historical heritage of the island;

51 (2) The need for ethical oversight, ethical statutory provisions, and conflict of interest

52 restrictions relating to the governing and development of the island; 53 (3) The need for greater input or control in the public policy and governance of the island

54 by the residents;

55 (4) The fairness and equality of property tax evaluations and assessments; and

56 (5) Access by and fair representation of the Geechee Gullah people in government public

57 policy effecting the island.

58 BE IT FURTHER RESOLVED that the committee may conduct such meetings at such

59 places and at such times as it may deem necessary or convenient to enable it to exercise fully

60 and effectively its powers, perform its duties, and accomplish the objectives and purposes

61 of this resolution. The members of the committee shall receive the allowances authorized

62 for legislative members of interim legislative committees but shall receive the same for not

63 more than five days unless additional days are authorized. The funds necessary to carry out

64 the provisions of this resolution shall come from the funds appropriated to the Senate. In the

65 event the committee makes a report of its findings and recommendations, with suggestions

66 for proposed legislation, if any, such report shall be made on or before December 31, 2013.

67 The committee shall stand abolished on December 31, 2013.

7 is managed by the Georgia Department of Natural Resources, while the remaining 3 percent

8 of the island is under private ownership; and

9 WHEREAS, the island also consists of the Sapelo Island National Estuarine Research

10 Reserve, the University of Georgia Marine Institute, and the Reynold's Mansion State Park;

11 and

12 WHEREAS, the Geechee Gullah people are the direct descendants of the slaves of Thomas

13 Spalding, who was the original landowner of Sapelo Island, and following the conclusion of

14 the Civil War, ownership of designated lands of the island were legally transferred to these

15 original freed men; and

16 WHEREAS, in 1983, Georgia law established the Sapelo Island Heritage Authority for the

17 purpose of preserving the culture in the endangered historical areas of Sapelo Island; and

18 WHEREAS, a severe erosion of Geechee Gullah culture and heritage has continued to the

19 point that it is in a state of near extinction; and

20 WHEREAS, extensive, unregulated commercial development of the island, without ethical

21 review or oversight, threatens not only the Geechee Gullah people but also the island's

22 beautiful natural resources and wildlife; and23 WHEREAS, such development has been for the personal, private gain of the few at the

24 expense of all of Georgia's citizens; and

25 WHEREAS, title to lands of the island is a matter of legal dispute, and the state's current

26 ownership may be the result of unjust enrichment at the expense of the Geechee Gullah

27 people; and

28 WHEREAS, the island has an abundance of historical property that is in need of state

29 funding for renovation and promotion as tourist attractions; and

30 WHEREAS, much of the island is composed of natural areas which need to be protected as

31 habitats for wildlife, nesting birds, and turtles in order to protect the beauty and tranquility

32 of this special state resource; and

33 WHEREAS, many concerned citizens, environmentalist groups, business and property

34 owners, and the original Geechee Gullah residents are gravely concerned about the future of

35 this beautiful island and the survival of its native people; and

36 WHEREAS, before it is too late and the important environmental and historical heritage of

37 the island is lost forever, the State of Georgia needs to immediately undertake an extensive

38 study and create a proposal for the development, funding, governance, and future of Sapelo

39 Island.40 NOW, THEREFORE, BE IT RESOLVED BY THE SENATE that there is created the Senate

41 Preservation of Sapelo Island Study Committee to be composed of seven members of the

42 Senate to be appointed by the President of the Senate. The President of the Senate shall

43 designate one of the members to serve as chairperson of the committee. The committee shall

44 meet at the call of the chairperson.

45 BE IT FURTHER RESOLVED that the committee shall undertake a study of the conditions,

46 needs, issues, and problems mentioned above or related thereto and recommend any actions

47 or legislation which the committee deems necessary or appropriate. The committee shall

48 review the following matters in particular:

49 (1) Building codes and zoning codes that may be needed for the protection of the

50 environment and the historical heritage of the island;

51 (2) The need for ethical oversight, ethical statutory provisions, and conflict of interest

52 restrictions relating to the governing and development of the island; 53 (3) The need for greater input or control in the public policy and governance of the island

54 by the residents;

55 (4) The fairness and equality of property tax evaluations and assessments; and

56 (5) Access by and fair representation of the Geechee Gullah people in government public

57 policy effecting the island.

58 BE IT FURTHER RESOLVED that the committee may conduct such meetings at such

59 places and at such times as it may deem necessary or convenient to enable it to exercise fully

60 and effectively its powers, perform its duties, and accomplish the objectives and purposes

61 of this resolution. The members of the committee shall receive the allowances authorized

62 for legislative members of interim legislative committees but shall receive the same for not

63 more than five days unless additional days are authorized. The funds necessary to carry out

64 the provisions of this resolution shall come from the funds appropriated to the Senate. In the

65 event the committee makes a report of its findings and recommendations, with suggestions

66 for proposed legislation, if any, such report shall be made on or before December 31, 2013.

67 The committee shall stand abolished on December 31, 2013.

The Island Packet

By GINA SMITH

[email protected]

843-706-8145

Published Thursday, January 3, 2013

Read more here: http://www.islandpacket.com/2013/01/03/2330293/bluffton-firm-wins-57-million.html#storylink=cpy

It's a great day for Bluffton-based BFG Communications, which will soon be awarded a $57 million contract with the state Department of Parks, Recreation and Tourism.

During the contract's six-and-a-half-year duration, the agency will be responsible for marketing the state's parks to visitors, with a focus on the undiscovered and unique experiences South Carolina offers.

"We look to the agency to bring the expertise, the technology, the media strategy to our marketing approach," said Marion Edmonds, PRT spokesman. "We were impressed with their creativity."

For nearly 30 years, the contract has been handled by Greenville-based Leslie Advertising and its successor, the bounce Agency, which is closing.

That set off a firestorm of competition for the big-dollar contract.

BFG was selected from a group of four finalists, all South Carolina ad agencies, Edmonds said.

The firm, which started in 1995, has more than 250 employees, and its clients include Coca-Cola, Warner Bros. Entertainment and Hanes Brands.

PRT's spring ad campaign is already set, but the public will see BFG's imprint beginning with the fall advertising effort. The new contract takes effect Jan. 15 after a standard 10-day period, during which the award can be protested.

"Our job will be simply to uncover these hidden gems and showcase them with all the passion we have for the friendly people, intriguing places and immense opportunities offered throughout this great state," Kevin Meany, BFG Communications president and CEO, said in a statement.

A $2.5 million media campaign gearing up this year is aimed at attracting visitors to lesser-known areas, including smaller towns people bypass on the way to more traditional tourist spots, state parks and rural attractions such as the Cherokee Foothills Trail and Jocassee Gorges.

Bruce Smith of The Associated Press contributed to this report.

Follow reporter Gina Smith at twitter.com/GinaNSmith.

Read more here: http://www.islandpacket.com/2013/01/03/2330293/bluffton-firm-wins-57-million.html#storylink=cpy

During the contract's six-and-a-half-year duration, the agency will be responsible for marketing the state's parks to visitors, with a focus on the undiscovered and unique experiences South Carolina offers.

"We look to the agency to bring the expertise, the technology, the media strategy to our marketing approach," said Marion Edmonds, PRT spokesman. "We were impressed with their creativity."

For nearly 30 years, the contract has been handled by Greenville-based Leslie Advertising and its successor, the bounce Agency, which is closing.

That set off a firestorm of competition for the big-dollar contract.

BFG was selected from a group of four finalists, all South Carolina ad agencies, Edmonds said.

The firm, which started in 1995, has more than 250 employees, and its clients include Coca-Cola, Warner Bros. Entertainment and Hanes Brands.

PRT's spring ad campaign is already set, but the public will see BFG's imprint beginning with the fall advertising effort. The new contract takes effect Jan. 15 after a standard 10-day period, during which the award can be protested.

"Our job will be simply to uncover these hidden gems and showcase them with all the passion we have for the friendly people, intriguing places and immense opportunities offered throughout this great state," Kevin Meany, BFG Communications president and CEO, said in a statement.

A $2.5 million media campaign gearing up this year is aimed at attracting visitors to lesser-known areas, including smaller towns people bypass on the way to more traditional tourist spots, state parks and rural attractions such as the Cherokee Foothills Trail and Jocassee Gorges.

Bruce Smith of The Associated Press contributed to this report.

Follow reporter Gina Smith at twitter.com/GinaNSmith.

Read more here: http://www.islandpacket.com/2013/01/03/2330293/bluffton-firm-wins-57-million.html#storylink=cpy

http://www.kickstarter.com/projects/1957876924/shadows-of-the-gullah

Descendants of enslaved Africans, the Gullah/Geechee are fighting to hold on to their land and culture in the face of development.

"Nothing is more noble in documentary photography than trying to save a culture from extinction. Following the history of the slave trade often leaves one wondering if the price of slavery paid in human sacrifice can ever be erased. Of course it cannot. One would hope that at least the vestiges of this most horrific assault on human dignity could at least be allowed its own evolution, its own peace.

Removed unwillingly from their own land and forced to live in another should at least bring a sense of humanistic responsibility on the descendants of the guilty to make sure at least that the hybrid culture be respected and preserved rather than be victimized yet again.

Good on you Pete for giving this important document your all. If you believe in this work, then it will not be wholly dependent on a fundraiser. If you believe in this work, you will figure out a way to keep going until a body of work emerges that will at least be some form of payback to the travesties of our forefathers.

Surely even the greatest essay you can ever make on the remaining Gullah population can justify the original sin, but at least it can be a testament to the positive side of the many faces of human nature."

– David Alan Harvey, Publisher of BURN Magazine, National Geographic Photograher and member of the MAGNUM photo agency.

WHY IT'S IMPORTANTAs the Gullah/Geechee lands are consumed by development, can their culture survive? Or will it be reduced to a tourist attraction or a relic of the past?

I moved to Beaufort, S.C. with my family in 1974 when my father, who was in the Marine Corps, was transferred to Parris Island.

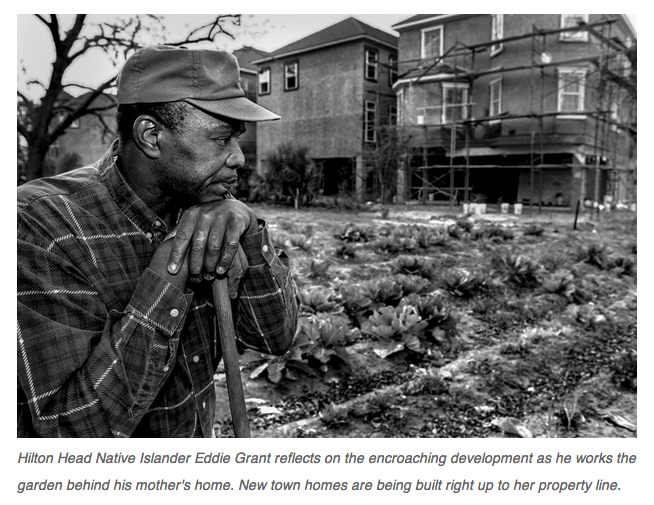

At age 13 I was quite unaware of the challenges of the Gullah/Geechee people. What I did see were the changes that were going on in nearby Bluffton and Hilton Head Island. I witnessed firsthand how the development of high-end residential communities known as plantations where taking over the land. I was just not conscious of the effect this was having on a community.

Later, living on Hilton Head Island, I met many Native Islanders. I have found them to be some of the most resilient people I have ever met. Proud of their heritage and determined to keep it alive.

Since the late 1950's the Gullah/Geechee people of the Sea Islands have been losing their lands due to sharply rising property taxes caused by resort development. They have struggled to prevent their culture, which is rooted in the land, from being assimilated.

Over the last 60 or 70 years other groups with centuries-old roots in America have been dragged into the mainstream, including the Cajuns, Highlanders, Native Americans.

Now the Gullah/Geechee are trying to hold on as best they can.

I need your help to tell this story.

THE STORYThe Sea Islands of South Carolina are home to a culture that is being consumed by golf courses, resorts and million-dollar homes. That culture is known as Gullah (known as Geechee in Georgia and Florida).

The Gullah people are direct decendents of enslaved Africans who were brought to the islands from West Africa. After arriving in America, the Gullah created their own community steeped in religion and African traditions. They also formed their own language also known as Gullah – a mix of Elizabethan English and African languages. "E aint crack a teet." Translation: "Hasn't said a word."

When slavery was abolished in 1863, the Gullah people of the Sea Islands remained on the land after slave owners abandoned the area. They continued their traditions – making sea grass baskets, burying their dead by the shore, farming vegetables and fruits and living life simply. Having lived this way for decades, the Gullah are believed to be one of the most authentic African American communities in the United States.

But development is now taking over these once isolated lands and consuming the Gullah way of life.

To witness this destruction, one needn't look further than the Gullah cemeteries, many of which have been taken over by privately owned gated communities and resorts known as plantations. Gullah who do not work for the plantations must ask for permission to even visit the cemeteries. The plantation owners will usually allow the Gullah on the land so long as an escort is available. If and escort is not available, the Gullah are not allowed to visit their relative's tombs.

Descendants of enslaved Africans, the Gullah/Geechee are fighting to hold on to their land and culture in the face of development.

"Nothing is more noble in documentary photography than trying to save a culture from extinction. Following the history of the slave trade often leaves one wondering if the price of slavery paid in human sacrifice can ever be erased. Of course it cannot. One would hope that at least the vestiges of this most horrific assault on human dignity could at least be allowed its own evolution, its own peace.

Removed unwillingly from their own land and forced to live in another should at least bring a sense of humanistic responsibility on the descendants of the guilty to make sure at least that the hybrid culture be respected and preserved rather than be victimized yet again.

Good on you Pete for giving this important document your all. If you believe in this work, then it will not be wholly dependent on a fundraiser. If you believe in this work, you will figure out a way to keep going until a body of work emerges that will at least be some form of payback to the travesties of our forefathers.

Surely even the greatest essay you can ever make on the remaining Gullah population can justify the original sin, but at least it can be a testament to the positive side of the many faces of human nature."

– David Alan Harvey, Publisher of BURN Magazine, National Geographic Photograher and member of the MAGNUM photo agency.

WHY IT'S IMPORTANTAs the Gullah/Geechee lands are consumed by development, can their culture survive? Or will it be reduced to a tourist attraction or a relic of the past?

I moved to Beaufort, S.C. with my family in 1974 when my father, who was in the Marine Corps, was transferred to Parris Island.

At age 13 I was quite unaware of the challenges of the Gullah/Geechee people. What I did see were the changes that were going on in nearby Bluffton and Hilton Head Island. I witnessed firsthand how the development of high-end residential communities known as plantations where taking over the land. I was just not conscious of the effect this was having on a community.

Later, living on Hilton Head Island, I met many Native Islanders. I have found them to be some of the most resilient people I have ever met. Proud of their heritage and determined to keep it alive.

Since the late 1950's the Gullah/Geechee people of the Sea Islands have been losing their lands due to sharply rising property taxes caused by resort development. They have struggled to prevent their culture, which is rooted in the land, from being assimilated.

Over the last 60 or 70 years other groups with centuries-old roots in America have been dragged into the mainstream, including the Cajuns, Highlanders, Native Americans.

Now the Gullah/Geechee are trying to hold on as best they can.

I need your help to tell this story.

THE STORYThe Sea Islands of South Carolina are home to a culture that is being consumed by golf courses, resorts and million-dollar homes. That culture is known as Gullah (known as Geechee in Georgia and Florida).

The Gullah people are direct decendents of enslaved Africans who were brought to the islands from West Africa. After arriving in America, the Gullah created their own community steeped in religion and African traditions. They also formed their own language also known as Gullah – a mix of Elizabethan English and African languages. "E aint crack a teet." Translation: "Hasn't said a word."

When slavery was abolished in 1863, the Gullah people of the Sea Islands remained on the land after slave owners abandoned the area. They continued their traditions – making sea grass baskets, burying their dead by the shore, farming vegetables and fruits and living life simply. Having lived this way for decades, the Gullah are believed to be one of the most authentic African American communities in the United States.

But development is now taking over these once isolated lands and consuming the Gullah way of life.

To witness this destruction, one needn't look further than the Gullah cemeteries, many of which have been taken over by privately owned gated communities and resorts known as plantations. Gullah who do not work for the plantations must ask for permission to even visit the cemeteries. The plantation owners will usually allow the Gullah on the land so long as an escort is available. If and escort is not available, the Gullah are not allowed to visit their relative's tombs.

The Gullah who live on the Sea Islands -- including Hilton Head Island, Daufuskie Island, and St. Helena Island -- have taken dozens of blows, and now their culture is in danger of becoming extinct.

The problem isn't unique to the Sea Islands of South Carolina, however.

The Geechee of Sapelo Island, Ga., are the latest to fall victim to encroaching development. Also descendants of slaves, the Geechee have for years been the only private landowners on Sapelo. The State of Georgia, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and the University of Georgia Marine Institute own rest of the land.

However, investors have begun to slowly and quietly purchase land on the island, causing county taxes to increase sharply and leaving many Geechee distraught as they struggle to preserve their way of life.

For instance, one 73-year-old resident paid $362 in property taxes in 2011 for her three-room home and acre of land. This year, her taxes increased to $2,312, according to The New York Times.

The Gullah/Geechee Coast extends for hundreds of miles between Cape Fear, N.C., and the St. Johns River in Florida. In 2004, the National Trust for Historic Preservation named the Gullah/Geechee Coast one of the 11 most endangered placed in the United States. "Unless something is done to halt the destruction, [the] Gullah/Geechee culture will be relegated to museums and history books, and our nation's unique cultural mosaic will lose on of its richest and most colorful pieces," states the National Trust Website.

THE PROJECTIf successfully funded, donations will be used to complete the photography over the next year. I am planning 5-7 trips to the Sea Islands over the next 12 months. Funding will be used for transportation, lodging, and everyday expenses while on the road.

After photography has been completed, I will select a "gallery" edit of 25-30 images to be framed for exhibition. A portion of the donations raised here will cover the cost of framing.

Once the framed exhibit is complete it will be made available to organizations and galleries that are interested in telling the Gullah/Geechee story. I have already received interest from some of the Gullah/Geechee organizations.

The exhibit will be offered free of charge with the exhibitor paying for shipping and insurance.

NOTES ON REWARDSAll of the prints being given as rewards are signed and numbered editions limited to 125 prints for each size offered. A portion of each edition will be reserved to be donated to Gullah/Geechee organizations.

RISKS AND CHALLENGESLearn about accountability on Kickstarter

I think the biggest "risk" would be for me not to do what I can through my photography to help bring attention to the plight of the Gullah/Geechee culture. Of America's 50 national heritage areas, the Gullah/Geechee Corridor is the only one that deals specifically with the African-American experience. Anything that can be done to help preserve this part of our nation's fabric, should be done.

Usually the most challenging part of working on projects such as this is gaining access to the community that you want to photograph. I have already cultivated relationships with the Gullah and Geechee community leaders on many of the Sea Islands, and they are supportive of my efforts to tell their story.

To date this project has been self-funded. I am looking for your support to complete this reportage. Donations will go toward transportation, lodging and general living expenses while on the road.

The images you see here are part of the photography I have already completed on this project. The images are from Hilton Head Island, Daufuskie Island and from time I spent with two Gullah shrimpers off the coast of South Carolina.

Along the Gullah/Geechee Coast, I plan to continue documenting how development and ignorance are destroying the Gullah/Geechee culture. Through images and text, I plan to focus on the challenges the Gullah/Geechee people face as they cling to their traditions and land while adjusting to the "progress" that is imposed upon them.

My goal is to publish this story in a book and multimedia format on the internet. I also intend to show the photography as a traveling exhibit. The exhibit will be loaned free of charge except for shipping and insurance fees.

Telling this story will emphasize the importance of preserving this culture and enlighten those who don't even know it exists.

The problem isn't unique to the Sea Islands of South Carolina, however.

The Geechee of Sapelo Island, Ga., are the latest to fall victim to encroaching development. Also descendants of slaves, the Geechee have for years been the only private landowners on Sapelo. The State of Georgia, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and the University of Georgia Marine Institute own rest of the land.

However, investors have begun to slowly and quietly purchase land on the island, causing county taxes to increase sharply and leaving many Geechee distraught as they struggle to preserve their way of life.

For instance, one 73-year-old resident paid $362 in property taxes in 2011 for her three-room home and acre of land. This year, her taxes increased to $2,312, according to The New York Times.

The Gullah/Geechee Coast extends for hundreds of miles between Cape Fear, N.C., and the St. Johns River in Florida. In 2004, the National Trust for Historic Preservation named the Gullah/Geechee Coast one of the 11 most endangered placed in the United States. "Unless something is done to halt the destruction, [the] Gullah/Geechee culture will be relegated to museums and history books, and our nation's unique cultural mosaic will lose on of its richest and most colorful pieces," states the National Trust Website.

THE PROJECTIf successfully funded, donations will be used to complete the photography over the next year. I am planning 5-7 trips to the Sea Islands over the next 12 months. Funding will be used for transportation, lodging, and everyday expenses while on the road.

After photography has been completed, I will select a "gallery" edit of 25-30 images to be framed for exhibition. A portion of the donations raised here will cover the cost of framing.

Once the framed exhibit is complete it will be made available to organizations and galleries that are interested in telling the Gullah/Geechee story. I have already received interest from some of the Gullah/Geechee organizations.

The exhibit will be offered free of charge with the exhibitor paying for shipping and insurance.

NOTES ON REWARDSAll of the prints being given as rewards are signed and numbered editions limited to 125 prints for each size offered. A portion of each edition will be reserved to be donated to Gullah/Geechee organizations.

RISKS AND CHALLENGESLearn about accountability on Kickstarter

I think the biggest "risk" would be for me not to do what I can through my photography to help bring attention to the plight of the Gullah/Geechee culture. Of America's 50 national heritage areas, the Gullah/Geechee Corridor is the only one that deals specifically with the African-American experience. Anything that can be done to help preserve this part of our nation's fabric, should be done.

Usually the most challenging part of working on projects such as this is gaining access to the community that you want to photograph. I have already cultivated relationships with the Gullah and Geechee community leaders on many of the Sea Islands, and they are supportive of my efforts to tell their story.

To date this project has been self-funded. I am looking for your support to complete this reportage. Donations will go toward transportation, lodging and general living expenses while on the road.

The images you see here are part of the photography I have already completed on this project. The images are from Hilton Head Island, Daufuskie Island and from time I spent with two Gullah shrimpers off the coast of South Carolina.

Along the Gullah/Geechee Coast, I plan to continue documenting how development and ignorance are destroying the Gullah/Geechee culture. Through images and text, I plan to focus on the challenges the Gullah/Geechee people face as they cling to their traditions and land while adjusting to the "progress" that is imposed upon them.

My goal is to publish this story in a book and multimedia format on the internet. I also intend to show the photography as a traveling exhibit. The exhibit will be loaned free of charge except for shipping and insurance fees.

Telling this story will emphasize the importance of preserving this culture and enlighten those who don't even know it exists.

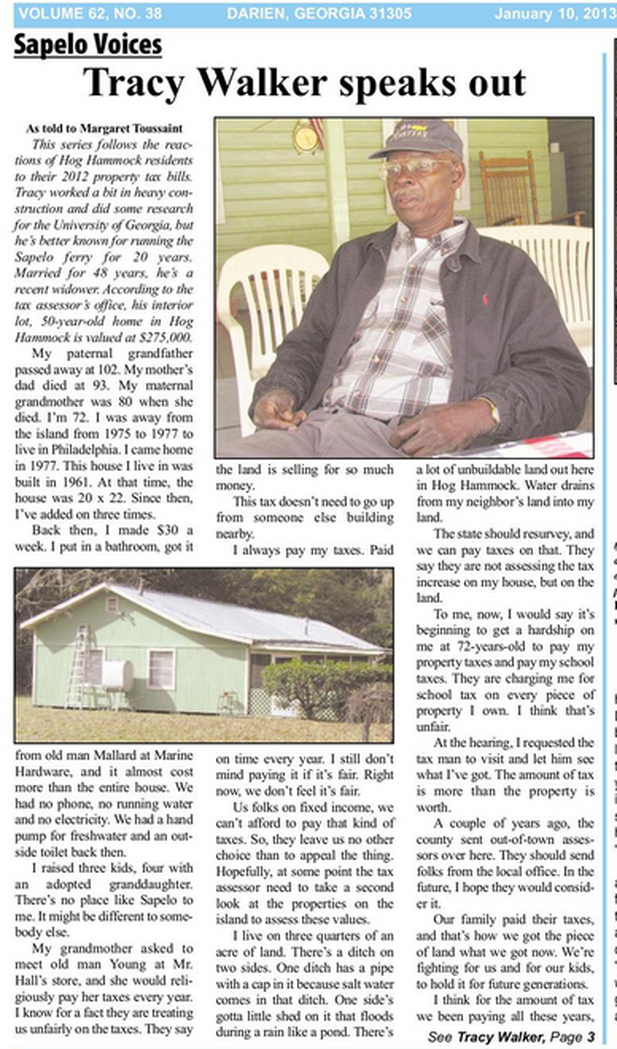

The Darien News

January 9, 2013

www.thedariennews.net

The Darien News

January 2, 2013

www.thedariennews.net