Public Policy Statement - Gullah/Geechee Culture Initiative

Released: Thursday, September 27, 2012

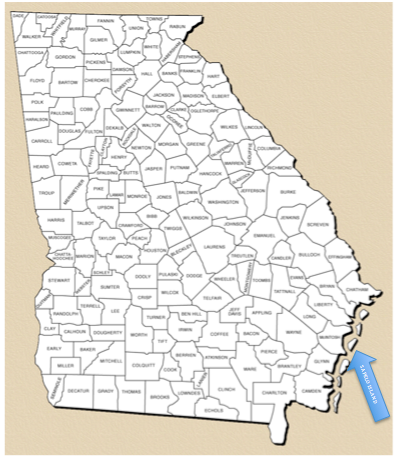

This Public Policy Statement represents the intent of the Gullah/Geechee Culture Initiative. The intention of this Public Policy Statement is to communicate the impact of The New York Times article on the situational outcomes of residents of Sapelo Island, published September 25, 2012 entitled “Taxes Threaten an Island Culture in Georgia.” The article puts on display bad management and property taxes that were kept artificially low by questionable policies in McIntosh County, Georgia. The bad management and questionable policies are the direct cause multi-generational Cultural Deprivation, specifically for the decedents of Sapelo Island.

The Gullah/Geechee Culture Initiative is designed to apply contemporary Public Policy Management Strategies for remedies, resolutions, and solutions for the future of Gullah/Geechee culture. Additionally, the Gullah/Geechee Culture Initiative provides a collaborative framework to identify research and collect reliable data to manage those strategies.

With The New York Times article as a starting point, critical Gullah/Geechee stakeholders can begin to impact a Cultural Regeneration Strategy that is sustainable both now and for generations to come.

It is within this context that the Gullah/Geechee Culture Initiative publishes this Public Policy Statement. This statement was constituted by Nationally/Internationally Certified Mediator Al Bartell, Public PolicyManagement with the Gullah Geechee Culture Initiative.

The Gullah/Geechee Culture Initiative is designed to apply contemporary Public Policy Management Strategies for remedies, resolutions, and solutions for the future of Gullah/Geechee culture. Additionally, the Gullah/Geechee Culture Initiative provides a collaborative framework to identify research and collect reliable data to manage those strategies.

With The New York Times article as a starting point, critical Gullah/Geechee stakeholders can begin to impact a Cultural Regeneration Strategy that is sustainable both now and for generations to come.

It is within this context that the Gullah/Geechee Culture Initiative publishes this Public Policy Statement. This statement was constituted by Nationally/Internationally Certified Mediator Al Bartell, Public PolicyManagement with the Gullah Geechee Culture Initiative.

Taxes Threaten an Island Culture in Georgia

SAPELO ISLAND, Ga. — Once the huge property tax bills started coming, telephones started ringing. It did not take long for the 50 or so people who live on this largely undeveloped barrier island to realize that life was about to get worse.

Sapelo Island, a tangle of salt marsh and sand reachable only by boat, holds the largest community of people who identify themselves as saltwater Geechees. Sometimes called the Gullahs, they have inhabited the nation’s southeast coast for more than two centuries. Theirs is one of the most fragile cultures in America.

These Creole-speaking descendants of slaves have long held their land as a touchstone, fighting the kind of development that turned Hilton Head and St. Simons Islands into vacation destinations. Now, stiff county tax increases driven by a shifting economy, bureaucratic bumbling and the unyielding desire for a house on the water have them wondering if their community will finally succumb to cultural erosion.

“The whole thing just smells,” said Jasper Watts, whose mother, Annie Watts, 73, still owns the three-room house with a tin roof that she grew up in.

She paid $362 in property taxes last year for the acre she lives on. This year, McIntosh County wants $2,312, a jump of nearly 540 percent.

Where real estate is concerned, history is always on the minds of the Geechees, who live in a place called Hog Hammock. It is hard for them not to be deeply suspicious of the tax increase and wonder if, as in the past, they are being nudged even further to the fringes.

Theirs is the only private land left on the island, almost 97 percent of which is owned by the state and given over to nature preserves, marine research projects and a plantation mansion built in 1802.

The tobacco heir R. J. Reynolds Jr. bought the mansion and most of the island during the Great Depression, persuading the Geechees who owned the rest to move to 400 swampy inland acres. Today, Hog Hammock is not much more than a collection of small houses and a historic cemetery, with a dusty general store and a part-time restaurant, Lula’s Kitchen, where shrimp and sausage are transformed into a low-country boil, a classic example of Sea Islands cooking.

That kind of history makes it hard for people to believe county officials who say there is no effort afoot to push them from the land. The county has offered 15 percent reductions in tax bills until the appeals that most people have filed can be heard. But it is going to be a challenge to pay even the reduced rate. While there is work cooking and cleaning for visitors to the plantation house, maintaining state research facilities or renting space to vacationers, money is difficult to find.

The relationship between Sapelo Island residents and county officials has long been strained, especially over race and development. In July, the community relations division of the Justice Department held two meetings with residents to address charges of racial discrimination. A department spokesman said the meetings were confidential and would not comment.

Neither would the chief tax appraiser, Rick Daniel, or other elected county officials. But Brett Cook, who manages the county and its only city, Darien, says local government does a lot to support the Geechee culture.

“It’s a wonderful history and a huge draw for our ecotourism,” he said.

This summer, he pointed out, the county worked with the Smithsonian to host a festival that culminated in a concert with members of the Atlanta Symphony Orchestra and the Geechee Gullah Ring Shouters, who practice a style of singing and hand claps developed by slaves.

The issue, said Mr. Cook and other county officials who would speak only if their names were not used, is not one of cultural genocide. They are just trying to clean up years of bad management and correct property taxes that were kept artificially low by questionable policies.

McIntosh County has a history of bureaucratic mistakes and election corruption. Its rocky political landscape was the subject of a book, “Praying for Sheetrock,” by Melissa Fay Greene, which detailed its racial segregation and the 1970s fight between a domineering white sheriff and people who wanted to elect the first black government official.

The county, which has about 14,000 year-round residents and thousands more with vacation homes, had for years put off reviewing its taxable property. An outside firm did the last valuation in 2004. Paul Griffin, the chairman of the Board of Tax Assessors, called the work “very, very sloppy” at a June meeting covered by The Darien News.

In 2009, the county was in the process of updating its tax digest when the state froze property taxes to help stanch the effects of the recession. Instead of continuing its work, the county stopped the process until this year.

Meanwhile, property was sold — some of it to wealthy people interested in vacation homes on the mainland and some on Sapelo Island. Those sales never made it to the tax records until now.

“We’re rural, we’re on the coast and we’re desirable,” Mr. Cook said. “When the market got hot six or seven years ago, a lot of individuals holding $15,000 or $20,000 lots on the marsh could sell them for $100,000 or $150,000.”

The county also started a new garbage pickup service and added other services, which contributed to the higher tax rates, he said. Sapelo Island residents, however, still have to haul their trash to the dump.

“Our taxes went up so high, and then you don’t have nothing to show for it,” said Cornelia Walker Bailey, the island’s unofficial historian. “Where is my fire department? Where are my water resources? Where is my paved road? Where are the things our tax dollars pay for?”

Here, where land is usually handed down or sold at below-market rates to relatives, Ms. Bailey has come to hold four pieces of property. She lives on one, which is protected from the tax increases by a homestead exemption. The rest will cost her 600 percent more in property taxes. “I think it’s an effort to erode everyone out of the last private sector of this island,” she said.

Government systems have been devised to try to save Sapelo Island’s Geechee culture. Hog Hammock is on the National Register of Historic Places, and the state created a Sapelo Island Heritage Authority in 1983, which the governor oversees. But critics contend that the authority could serve as a vehicle to more development.

State lawmakers have discussed creating a trust that would protect land from development but allow residents who could not afford to keep their property to stay. But that is still just an idea.

The National Park Service recently released a 272-page management plan for the Gullah Geechee Cultural Heritage Corridor, which stretches from Wilmington, N.C., to Jacksonville, Fla. It calls for creative solutions to preserving Gullah land, said Michael Allen, the service’s foremost expert on the community, of which he is also a member.

But it says nothing about how to fight the tax collector.

State Senator William Ligon, who represents the county and is a real estate lawyer, suggests that residents file a lawsuit if they do not get relief.

“In an economy where property values have been declining, I think I would want to look very, very closely at what had been done at the county level,” he said.

None of that offers immediate relief to residents who have tax bills piled up on kitchen tables and in desk drawers.

Sharron Grovner, 44, is one of them. Her mother, Lula Walker, runs the little restaurant on the island. Ms. Grovner buried her father not too long ago. Her family has more than four acres of property and faces more than $6,000 in taxes. Like most, they have appealed. “You can do the best you can do for a year, but then you are going to need some kind of help,” she said.

Still, they are not going to let go of the land. “It’s like this,” she said. “People like me don’t sell their property.”

A version of this article appeared in print on September 26, 2012, on page A16 of the New York edition with the headline:

Taxes Threaten Community Descended From Slaves.

Sapelo Island, a tangle of salt marsh and sand reachable only by boat, holds the largest community of people who identify themselves as saltwater Geechees. Sometimes called the Gullahs, they have inhabited the nation’s southeast coast for more than two centuries. Theirs is one of the most fragile cultures in America.

These Creole-speaking descendants of slaves have long held their land as a touchstone, fighting the kind of development that turned Hilton Head and St. Simons Islands into vacation destinations. Now, stiff county tax increases driven by a shifting economy, bureaucratic bumbling and the unyielding desire for a house on the water have them wondering if their community will finally succumb to cultural erosion.

“The whole thing just smells,” said Jasper Watts, whose mother, Annie Watts, 73, still owns the three-room house with a tin roof that she grew up in.

She paid $362 in property taxes last year for the acre she lives on. This year, McIntosh County wants $2,312, a jump of nearly 540 percent.

Where real estate is concerned, history is always on the minds of the Geechees, who live in a place called Hog Hammock. It is hard for them not to be deeply suspicious of the tax increase and wonder if, as in the past, they are being nudged even further to the fringes.

Theirs is the only private land left on the island, almost 97 percent of which is owned by the state and given over to nature preserves, marine research projects and a plantation mansion built in 1802.

The tobacco heir R. J. Reynolds Jr. bought the mansion and most of the island during the Great Depression, persuading the Geechees who owned the rest to move to 400 swampy inland acres. Today, Hog Hammock is not much more than a collection of small houses and a historic cemetery, with a dusty general store and a part-time restaurant, Lula’s Kitchen, where shrimp and sausage are transformed into a low-country boil, a classic example of Sea Islands cooking.

That kind of history makes it hard for people to believe county officials who say there is no effort afoot to push them from the land. The county has offered 15 percent reductions in tax bills until the appeals that most people have filed can be heard. But it is going to be a challenge to pay even the reduced rate. While there is work cooking and cleaning for visitors to the plantation house, maintaining state research facilities or renting space to vacationers, money is difficult to find.

The relationship between Sapelo Island residents and county officials has long been strained, especially over race and development. In July, the community relations division of the Justice Department held two meetings with residents to address charges of racial discrimination. A department spokesman said the meetings were confidential and would not comment.

Neither would the chief tax appraiser, Rick Daniel, or other elected county officials. But Brett Cook, who manages the county and its only city, Darien, says local government does a lot to support the Geechee culture.

“It’s a wonderful history and a huge draw for our ecotourism,” he said.

This summer, he pointed out, the county worked with the Smithsonian to host a festival that culminated in a concert with members of the Atlanta Symphony Orchestra and the Geechee Gullah Ring Shouters, who practice a style of singing and hand claps developed by slaves.

The issue, said Mr. Cook and other county officials who would speak only if their names were not used, is not one of cultural genocide. They are just trying to clean up years of bad management and correct property taxes that were kept artificially low by questionable policies.

McIntosh County has a history of bureaucratic mistakes and election corruption. Its rocky political landscape was the subject of a book, “Praying for Sheetrock,” by Melissa Fay Greene, which detailed its racial segregation and the 1970s fight between a domineering white sheriff and people who wanted to elect the first black government official.

The county, which has about 14,000 year-round residents and thousands more with vacation homes, had for years put off reviewing its taxable property. An outside firm did the last valuation in 2004. Paul Griffin, the chairman of the Board of Tax Assessors, called the work “very, very sloppy” at a June meeting covered by The Darien News.

In 2009, the county was in the process of updating its tax digest when the state froze property taxes to help stanch the effects of the recession. Instead of continuing its work, the county stopped the process until this year.

Meanwhile, property was sold — some of it to wealthy people interested in vacation homes on the mainland and some on Sapelo Island. Those sales never made it to the tax records until now.

“We’re rural, we’re on the coast and we’re desirable,” Mr. Cook said. “When the market got hot six or seven years ago, a lot of individuals holding $15,000 or $20,000 lots on the marsh could sell them for $100,000 or $150,000.”

The county also started a new garbage pickup service and added other services, which contributed to the higher tax rates, he said. Sapelo Island residents, however, still have to haul their trash to the dump.

“Our taxes went up so high, and then you don’t have nothing to show for it,” said Cornelia Walker Bailey, the island’s unofficial historian. “Where is my fire department? Where are my water resources? Where is my paved road? Where are the things our tax dollars pay for?”

Here, where land is usually handed down or sold at below-market rates to relatives, Ms. Bailey has come to hold four pieces of property. She lives on one, which is protected from the tax increases by a homestead exemption. The rest will cost her 600 percent more in property taxes. “I think it’s an effort to erode everyone out of the last private sector of this island,” she said.

Government systems have been devised to try to save Sapelo Island’s Geechee culture. Hog Hammock is on the National Register of Historic Places, and the state created a Sapelo Island Heritage Authority in 1983, which the governor oversees. But critics contend that the authority could serve as a vehicle to more development.

State lawmakers have discussed creating a trust that would protect land from development but allow residents who could not afford to keep their property to stay. But that is still just an idea.

The National Park Service recently released a 272-page management plan for the Gullah Geechee Cultural Heritage Corridor, which stretches from Wilmington, N.C., to Jacksonville, Fla. It calls for creative solutions to preserving Gullah land, said Michael Allen, the service’s foremost expert on the community, of which he is also a member.

But it says nothing about how to fight the tax collector.

State Senator William Ligon, who represents the county and is a real estate lawyer, suggests that residents file a lawsuit if they do not get relief.

“In an economy where property values have been declining, I think I would want to look very, very closely at what had been done at the county level,” he said.

None of that offers immediate relief to residents who have tax bills piled up on kitchen tables and in desk drawers.

Sharron Grovner, 44, is one of them. Her mother, Lula Walker, runs the little restaurant on the island. Ms. Grovner buried her father not too long ago. Her family has more than four acres of property and faces more than $6,000 in taxes. Like most, they have appealed. “You can do the best you can do for a year, but then you are going to need some kind of help,” she said.

Still, they are not going to let go of the land. “It’s like this,” she said. “People like me don’t sell their property.”

A version of this article appeared in print on September 26, 2012, on page A16 of the New York edition with the headline:

Taxes Threaten Community Descended From Slaves.

Six years ago, Congress took note of one of the nation’s great sagas of endurance — descendants of slavery who survived for generations on the barrier chain of Sea Islands along the southeast coast. The government created a cultural heritage corridor from North Carolina to Florida to celebrate the Gullah and Geechee peoples, as they are known.

It is sadly ironic that one of the last intact communities — the saltwater Geechees of Hog Hammock on Sapelo Island off Georgia — now must fight for its historic landhold in the face of a sudden burst of exorbitant real estate taxes from local government.

“The whole thing just smells,” Jasper Watts told Kim Severson of The Times. His family faced a 500-percent-plus tax increase on her house. Some in the doughty community of about 50 people received even bigger bills. Local officials insisted that their only intent is to reform badly outdated tax rates. The explanation is understandably questioned by Geechees who fear a move is afoot to force them to abandon their land to the wave of resort development that has been eroding Gullah-Geechee culture with gated communities and endless golf courses.

Hog Hammock is itself a last redoubt, one small part of an island that has been mostly claimed by the State of Georgia for research and education. Although the Geechees have endured through two centuries of slavery and Jim Crow suppression, they need and deserve help in their latest stand, if it is not to be their last.

State lawmakers have vaguely discussed a trust to help keep hard-pressed Geechees on their land. Something more certain is needed from state and local officials who don’t hesitate to feature the Geechees’ heritage in tourism marketing. It would be the nation’s loss if the corridor should lose its living vestige of a noble heritage.

A version of this editorial appeared in print on September 27, 2012, on page A28 of the New York edition with the headline:

Surviving Where Slaves Held Fast.

It is sadly ironic that one of the last intact communities — the saltwater Geechees of Hog Hammock on Sapelo Island off Georgia — now must fight for its historic landhold in the face of a sudden burst of exorbitant real estate taxes from local government.

“The whole thing just smells,” Jasper Watts told Kim Severson of The Times. His family faced a 500-percent-plus tax increase on her house. Some in the doughty community of about 50 people received even bigger bills. Local officials insisted that their only intent is to reform badly outdated tax rates. The explanation is understandably questioned by Geechees who fear a move is afoot to force them to abandon their land to the wave of resort development that has been eroding Gullah-Geechee culture with gated communities and endless golf courses.

Hog Hammock is itself a last redoubt, one small part of an island that has been mostly claimed by the State of Georgia for research and education. Although the Geechees have endured through two centuries of slavery and Jim Crow suppression, they need and deserve help in their latest stand, if it is not to be their last.

State lawmakers have vaguely discussed a trust to help keep hard-pressed Geechees on their land. Something more certain is needed from state and local officials who don’t hesitate to feature the Geechees’ heritage in tourism marketing. It would be the nation’s loss if the corridor should lose its living vestige of a noble heritage.

A version of this editorial appeared in print on September 27, 2012, on page A28 of the New York edition with the headline:

Surviving Where Slaves Held Fast.